I started up from the little commoosie beyond the fire, at Gillie’s excited cry, and ran to join him on the shore. A glance out over Caribou Point to the big bay, where innumerable whitefish were shoaling, showed me another chapter in a long but always interesting story. Ismaquehs, the fish-hawk, had risen from the lake with a big fish, and was doing his best to get away to his nest, where his young ones were clamoring. Over him soared the eagle, still as fate and as sure, now dropping to flap a wing in Ismaquehs’ face, now touching him with his great talons gently, as if to say, “Do you feel that, Ismaquehs? If I grip once ’t will be the end of you and your fish together. And what will the little ones do then, up in the nest on the old pine? Better drop him peacefully; you can catch another.—Drop him! I say.”

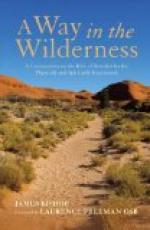

[Illustration: Ismaquehs]

Up to that moment the eagle had merely bothered the big hawk’s flight, with a gentle reminder now and then that he meant no harm, but wanted the fish which he could not catch himself. Now there was a change, a flash of the king’s temper. With a roar of wings he whirled round the hawk like a tempest, bringing up short and fierce, squarely in his line of flight. There he poised on dark broad wings, his yellow eyes glaring fiercely into the shrinking soul of Ismaquehs, his talons drawn hard back for a deadly strike. And Simmo the Indian, who had run down to join me, muttered: “Cheplahgan mad now. Ismaquehs find-um out in a minute.”

But Ismaquehs knew just when to stop. With a cry of rage he dropped, or rather threw, his fish, hoping it would strike the water and be lost. On the instant the eagle wheeled out of the way and bent his head sharply. I had seen him fold wings and drop before, and had held my breath at the speed. But dropping was of no use now, for the fish fell faster. Instead he swooped downward, adding to the weight of his fall the push of his strong wings, glancing down like a bolt to catch the fish ere it struck the water, and rising again in a great curve—up and away steadily, evenly as the king should fly, to his own little ones far away on the mountain.

Weeks before, I had had my introduction to Old Whitehead, as Gillie called him, on the Madawaska. We were pushing up river on our way to the wilderness, when a great outcry and the bang-bang of a gun sounded just ahead. Dashing round a wooded bend, we came upon a man with a smoking gun, a boy up to his middle in the river, trying to get across, and, on the other side, a black sheep running about baaing at every jump.

“He’s taken the lamb; he’s taken the lamb!” shouted the boy. Following the direction of his pointing finger, I saw Old Whitehead, a splendid bird, rising heavily above the tree-tops across the clearing. Reaching back almost instinctively, I clutched the heavy rifle which Gillie put into my hand and jumped out of the canoe; for with a rifle one wants steady footing. It was a long shot, but not so very difficult; Old Whitehead had got his bearings and was moving steadily, straight away. A second after the report of the rifle, we saw him hitch and swerve in the air; then two white quills came floating down, and as he turned we saw the break in his broad white tail. And that was the mark that we knew him by ever afterwards.