|

This section contains 2,176 words (approx. 6 pages at 400 words per page) |

|

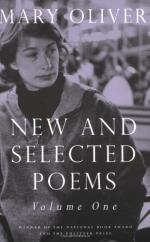

New and Selected Poems Summary & Study Guide Description

New and Selected Poems Summary & Study Guide includes comprehensive information and analysis to help you understand the book. This study guide contains the following sections:

This detailed literature summary also contains Topics for Discussion and a Free Quiz on New and Selected Poems by Mary Oliver.

Percy (the dog)

Percy, whose head is "wild and curly" is the poet's new dog who was named for "the beloved poet" Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822). Percy is the subject of three separate poems, each of which is devoted to revealing something wise and fairly mystical about the energetic black little dog.

In the first of the three selections, entitled Percy (One), the dog chews up a book which the poet admits was "left unguarded." This event turns out to be less than a tragedy when the reader is told that, luckily, Percy chewed up a book of which there are multiple copies available. The owner interprets Percy"s choice of ubiquitous book as wise and he receives praise, "Oh wisest of little dogs" (pg. 19).

Next, the reader encounters the little black dog in "Percy (Two)," a poem with an overtly political sentiment. The poem opens with, "I have a little dog who likes to nap with me." Following this, the reader is informed of Percy's virtues. He is "sweeter than soap," and "more wonderful than a diamond necklace." The poem continues with the speaker expressing a desire to introduce Percy to people in the world who are suffering, "that the sorrowing thousands might see his laughing mouth." It is apparent that the poet experiences Percy as a being whose presence is soothing, healing, and a great comfort to those with whom he spends time. The final lines of the poem directly criticize former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. The poet voices a desire to "take [Percy] to Washington, right into the Oval office," giving Rumsfeld the opportunity to "crawl out of [President Bush's] armpit." Similar to his effect on the poet herself, Oliver is convinced that frolicking with Percy with a moment would return Rumsfeld to the condition of "a rational man."

Percy makes his final (named) appearance in "Little Dog's Rhapsody in the Night (Percy Three)." Here, the reader is given a glimpse into Percy's ability to "ask for" and receive affection from his owner by rolling over on his back, "his four paws in the air." With what is described as a "fervent" look in his eyes, Percy seems to be saying, "Tell me you love me [...] / Tell me again." The poet finds Percy's request for attention irresistible and the relationship between dog and owner ("Could there be a sweeter arrangement?") is established as something which, in its repetition, fulfills both creatures.

Toadappears in Page 164

The toad symbolizes the innate wisdom of the natural world. In other words, the toad's lack of interaction with the poet shows that he has somehow managed to relate to other creatures outside of language and is none the worse for wear. It is the poet's human arrogance which leads her to believe that the toad is interested in what she has to say. The last line shows that the poet understands the toad's silence by referring to "the refined anguish of language." These words prove that even the poet knows that in some instances, language is simply not enough.

Likening the toad to the Buddha gives the creature an air of quiet sagacity that goes beyond mere conversation. As such, the reader is left with the impression that if it could speak to the poet, the toad's words would be few, but the message would be profound. His bulging, gold-rimmed eyes seem to be guarding a secret which has nothing to do with spoken language. The toad remains silent and still, patiently giving the poet a chance to say what she needs to say. It is almost as if the toad understands that the words coming out of the poet's mouth, while completely meaningless in his estimation, are nevertheless very important to the woman speaking. The inscrutable toad realizes the speaker's egotism as she talks on and on about herself and her human experience but he still allows her to prattle on. There is more to the "sand-colored" toad than meets the eye.

Sea Mouseappears in Page 167

What distinguishes the sea mouse from the other creatures described in this volume is its pitiable ugliness. The poet uses grotesque phrases like "the soaked mat of what was almost fur" and "toothless, legless, earless too" to describe the unfortunate drowned little victim she finds at the seashore. However, even in its unsightliness, the sea mouse is nonetheless recognized as rather unique and graceful. The animal's ugliness becomes secondary to the poet's affection for its being: "I stroked it, / tenderly, little darling, little dancer [...]" The poet's tender description of the ugly little sea mouse, "all delicate and revolting," elevates its status in the natural world. The reader is encouraged to look beyond the external and realize the juxtaposition which rests in all natural phenomena. There is an element of the sublime in the helpless dead creature. The limitless beauty that lives side-by-side with the cold horror of Nature is one of the great paradoxes of life.

Williamappears in Page 169

Although William is a human child, the poet nevertheless describes him in terms of creatures in the non-human realm: "He comes pecking, like a bird, at my / heart. His eyebrows are like the feathers of a wren." Interestingly enough, this description transports the child from ordinary human-ness to somehow mysterious and otherworldly. With "ears like seashells," William is bound to be someone special when he grows up as the sea denotes depth and ancient wisdom. As might be expected, the poet analogizes herself as well, saying: "I feel myself begin to wilt, like an old flower, weak in the / stem." Thus, the reader learns that the poet's sense of wonderment is not limited to flowers and woodland creatures alone. However, unlike the creatures she encounters on her outings in Nature, the poet admits her weakness for this human child. William's presence reminds Oliver of her vulnerability. She knows that at some point, William will become another entity who needs and wants; who demands and takes. Similarly, the poet understands that it will be her foolish pleasure to relinquish everything she has simply to ensure his continuity.

Winstonappears in Page 149

Described as "a big dog" of indeterminate breed, the poet comes upon Winston in the moments just before dawn. The scenario of "Beside he Waterfall" entails Winston dragging a young dead fawn ("scarcely larger than a rabbit") out of some foliage and eating it while she watches. There is no malice in Winston's behavior he simply follows what he knows to be a natural directive. Thus, the portrait of the dog painted by Oliver's language is extremely compassionate. The fact that Winston has "kind eyes" automatically mitigates any hostility one might register at the sight of him devouring the "flower-like head" of a fawn. Winston is without pretense; he didn't kill the young animal, but he has taken it upon himself to complete the cycle. Life and death to a dog such as Winston are nothing more than points on a continuum. His recognition of the fawn as dead functions only as a signal that it is acceptable that the fawn be eaten. Winston, and all other creatures, can be forgiven for following a predetermined path.

Billappears in Page 138

Bill is an acquaintance of the poet; someone she sees "only occasionally." This is evident from the poet's gauzy description of the man. There are not many details given about Bill himself, which lets the reader know that Oliver does not know him very well. Her representation of Bill is more like a dotted line drawing than a complete recollection. He owns an antique shop "on the main hot highway to Charlottesville." His wife is deceased and he has a son who seems to stay close-by. The son is beginning to look more like Bill's wife each day. In the back of the antique shop are things which are unfit to sell, like "bits of rusty metal, and odd pieces of china, a cup or a / plate with a fraction of its design still clear [...]" Like the odds and ends at the rear of the shop, Bill himself is something of a lost soul. The piece gives the reader an impression of Bill as a sweet, shy, melancholy kind of person. The way the poet recounts Bill's story about a mockingbird that takes cherries out of a bowl on the front stoop and returns them to the ground under the tree strikes a bittersweet chord. Bill is incomplete in the poet's mind and therefore incomplete in the reader's mind's eye as well.

Benjaminappears in Page 11

Benjamin is another dog who comes under the watchful observance of the poet/speaker. There is no specific physical description of Benjamin given in the poem. Rather, the poet endearingly paints the dog as a creature among other creatures; one who is unaware of the interconnectedness of things in Nature. Oliver writes of Benjamin, "No use to tell him that he and the raccoon are brothers," which implies that even if he could understand his position in the animal world, he would probably remained unconcerned. Here, Benjamin is the predator. He suffers no pangs of conscience in his desire to catch, and ultimately kill, the raccoon. As is the case with so many of the creatures Oliver writes about, Benjamin is simply being Benjamin. It is this inhabiting of the true essential self which is at odds with Oliver's concern for the raccoon's safety. This preoccupation with the hunter/hunted dichotomy is, the reader learns, a luxury available only to humans.

Miss Violetappears in Page 5

While not a character per se; Miss Violet is nonetheless an exquisite example of anthropomorphism. That is, Oliver attributes human traits and characteristics to an inanimate object; in this case, a flower. As a character, Miss Violet is a lonely lady who dresses to impress. The fact that "[s]he sits / in the mossy weeds and waits / to be noticed" tells the reader that this character thrives on the attention of others. Miss Violet wouldn't put on her "dress the color of sunlight" for her own individual pleasure, but to be admired and loved. Miss Violet could be a middle-aged or older lady who hungers for the affection of someone younger: "She loves especially to be picked by [...] young fingers, entranced by what has happened to the world." As such, Miss Violet becomes a figure who has seen a great deal of life and has perhaps become jaded by her experiences. She is a character who is invigorated by the touch of one more innocent than herself. The reader learns that Miss Violet's search for love is something which happens regularly: "We [...] call it Spring and we have been through it many times." This situates the character as hopeful and sympathetic. Each spring, Miss Violet once again feels excitement about the newness of a season of the heart.

Morningappears in Pages 30, 71, 124, 175

Morning is more than just the beginning of the day. It is emblematic of the fullness and the possibility of life and one's capacity to take it all in. Morning is a time of opportunity to see things clearly before the busyness of the day commences. Morning is a treasured time for Oliver, as she makes her way into a completely new set of observances and small wonders. Besides giving one the chance to watch the world awaken, morning also furnishes quiet time for reflecting on what has passed; days, weeks, months or years, and how time neatly fits into itself every time the sun rises. Morning ushers in life as well as death, and as such, is a mystery unto itself. One morning may appear to be much like another, and yet, each day brings with it the element of surprise. Neither good nor bad, morning means more than watching the moon set or hearing the birds sing after a long night of silence.

Mountain Lionappears in Page 28

Oliver's description of a mountain cat she encounters borders on the fantastic. "She stepped from under a cloud," gives the reader the impression that the cat is mythical and extremely rare. Unlike anything else in Nature, truly magnificent, "[h]er wide face / was a plate of gold [...] her shoulders shook like water [...]"gives the impression that the poet considers herself fortunate to finally be catching even a small glimpse of the creature. The poet's tone sets the cat before the reader as the Other; a prize specimen or an oddity not often seen by intruders who visit "the last unviolated mountains [...]." The poet seems aware of trespassing on the cat's territory and threatening the animal's feeling of safety. She writes: "When she saw that I saw her, instantly flames leaped in her eyes [...]" As punishment for accidentally sighting the cat, the poet comes to doubt her experience and reassesses the animal as "a lean and perfect mystery that perhaps I didn't see [...]" The poet comes to an understanding that the cat may well be wild but not as free as one would imagine, given the surprising nature of their chance meeting and the cat's reaction to being found in its once-secure habitat.

Read more from the Study Guide

|

This section contains 2,176 words (approx. 6 pages at 400 words per page) |

|