|

|

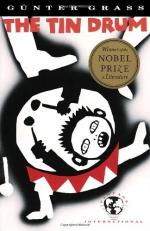

The Tin Drum Chapter 3: Moth and Light Bulb

In the mental institution, Oskar reads Bruno a portion of what he has written concerning his grandfather. Bruno says it is "A beautiful death" and begins to recreate the story with his knotted string art.

Oskar is visited by his two friends, Klepp (Egon Münzer) and Vittlar (Gottfried von Vittlar). Klepp brings Oskar a jazz recording, and Vittlar brings him a chocolate heart on a pink ribbon. They parody scenes from Oskar's trial (alluded to here and explained later - see below). Oskar tells them the story of his grandfather Koljaiczek. In response, Klepp makes swimming motions and shakes his head. Vittlar accuses Oskar of being the murderer, he says because Koljaiczek must have known that it would be wholly too burdensome to have a living grandfather. He adds that his grandfather's punishment to Oskar and his family was to not give them the satisfaction of having a corpse. Then he says that once Oskar is released, the myth about America gives Oskar an aim - for America is "the land where people find whatever they have lost, even missing grandfathers." Chapter 3, pg. 39.

Oskar returns to drumming out his family's story. Once Joseph Koljaiczek drowned, his elder brother, Gregor Koljaiczek, stays on with the widow Anna Bronski. He had never known his younger brother very well, but after a year, she and Gregor were married, as Oskar says, because he was a Koljaiczek. He worked in a gunpowder factory, but Anna was forced into renting a smaller apartment and selling miscellaneous items for money downstairs from the apartment in a cellar store, because Gregor drank away all his pay. He drank, Oskar says, not because he was sad or happy, but rather because he was a thorough man, unable to leave even a drop in a glass or bottle. Gregor finally died of the flu in 1917.

Jan Bronski, Agnes' cousin, later moved into the empty room with Anna and Agnes. He had finished high school and had taken on an apprentice job at the main post office in Danzig. He was twenty but still sickly, and thus couldn't pass his army physical when drafted, four times in all, into WWI. It was then that Agnes first fell in love with him - this was the beginning of a lifelong love affair between the two. Jan transferred to the Polish Post Office and moved in to the apartment only when Agnes' relationship with Alfred Matzerath became known to him. Alfred was a WWI veteran, whom Agnes had met while working as a nurse in WWI. Alfred had been shot through the thigh. He was a staunch supporter of Hitler and a citizen of the German Reich. In 1920, Agnes and Alfred were engaged, and Anna left the cellar store to them and moved in with her brother Vincent Bronski, back to her potato fields. Alfred and Agnes were married in 1923. In the meantime, Jan Bronski met and married Hedwig Bronski. It was then, after all four of them had met by chance in a cafe, that Jan and Alfred became friends, and Jan and Agnes lifelong lovers.

Once married, Alfred and Agnes bought a failing grocery store and turned it around. The two were perfect professional partners - Agnes worked behind the counter, and Alfred dealt with wholesalers. In addition, Matzerath was incredibly fond of all kitchen work - cooking, cleaning, etc. The couple moved into the flat adjoining the store. Oskar makes a point of asking his drum the wattage of the light bulbs in the bedroom of that apartment. Satisfied that the lights he first saw were two sixty-watt bulbs, he speaks of his birth. His mother gave birth at home. Oskar says that he was one of those infants whose mental development was completed at birth - it needed only "a certain amount of filling in." Seeing that it is a boy, Matzerath says that Oskar will take over the store when he is older. Agnes, Oskar's mother, says simply that when Oskar is three, he will have a toy drum. Weighing these two reactions, Oskar notices a moth darting between the two sixty watt light bulbs. He writes of the sound the moth made as a dialogue between the moth and the light bulb conferring some sort of absolution to the moth. He says:

"Today Oskar says simply: The moth drummed. I have heard rabbits, foxes, and dormice drumming. Frogs can drum up a storm. Woodpeckers are said to drum worms out of their hiding places. And men beat on basins, tin pans, bass drums, and kettledrums. We speak of drumfire, drumhead courts; we drum up, drum out, drum into. There are drummer boys and drum majors. There are composers who write concerti for strings and percussion. I might even mention Oskar's own efforts on the drum; but all this is nothing beside the orgy of drumming carried on by that moth in the hour of my birth, with no other instrument than two ordinary sixty-watt bulbs. Perhaps there are Negroes in darkest Africa and others in America who have not yet forgotten Africa who, with their well-known gift of rhythm, might succeed, in imitation of African moths - which are known to be larger and more beautiful than those of eastern Europe - in drumming with such disciplined passion; I can only go by my Eastern European standards and praise that medium-sized powdery-brown moth of the hour of my birth; that moth was Oskar's master." Chapter 3, pg. 48

Topic Tracking: Individuality/Identity 3

Topic Tracking: Individuality/Identity 4

Wailing and acting like a normal baby, Oskar decided to reject Matzerath's (who assumed he was Oskar's father) plans, and to go with his mother's plans. Oskar says it was only the promise of the drum that kept his from demanding a return to the womb.